Category Archives for Sketching

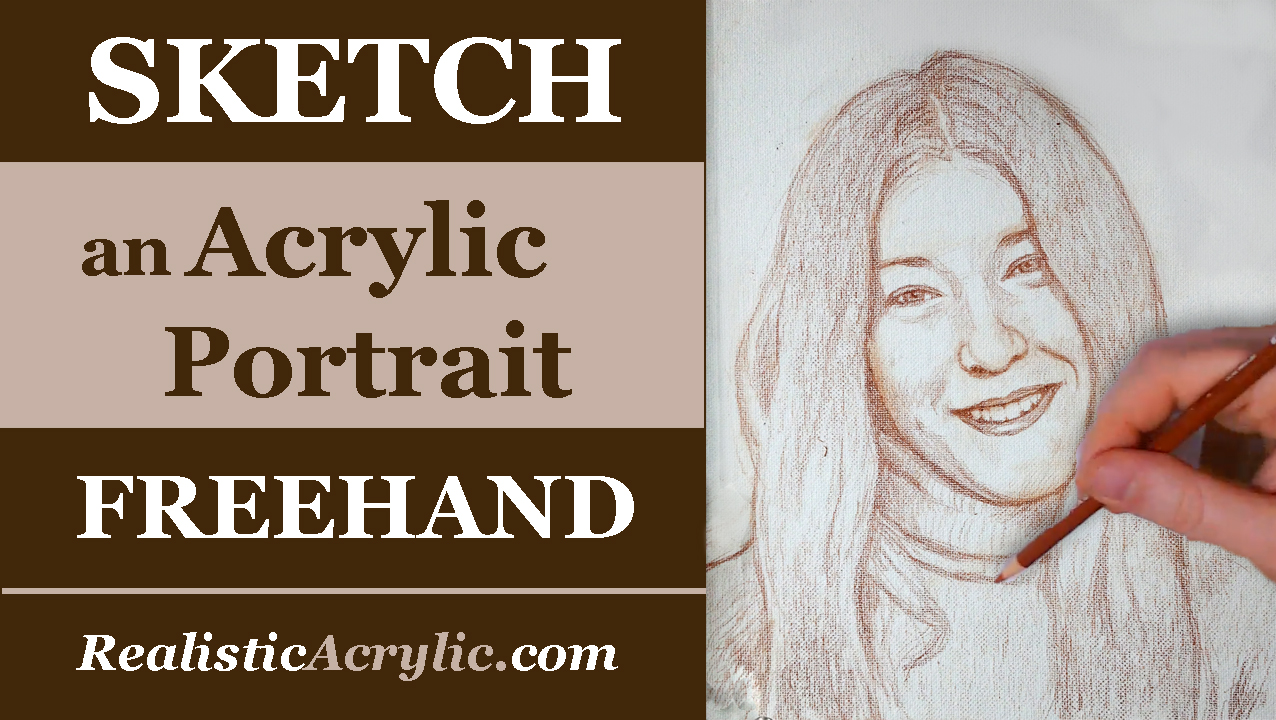

5 Steps to Sketch an Acrylic Portrait Freehand

Using a grid or tracing can be a great way for artists just starting out in portrait painting to create a lifelike, accurate sketch. It also can help experienced painters either save time or get their proportions a bit more accurate so they can concentrate more on their painting process.

But sometimes, it’s fun to just “throw off the training wheels” and do your sketch freehand. In fact, drawing freehand will enhance your ability to see intricate spacial relationships, shapes and contours that are vital at any stage in your painting.

You’ll learn to capture those small nuances that will make a person look like them.

What is the best way to draw freehand?

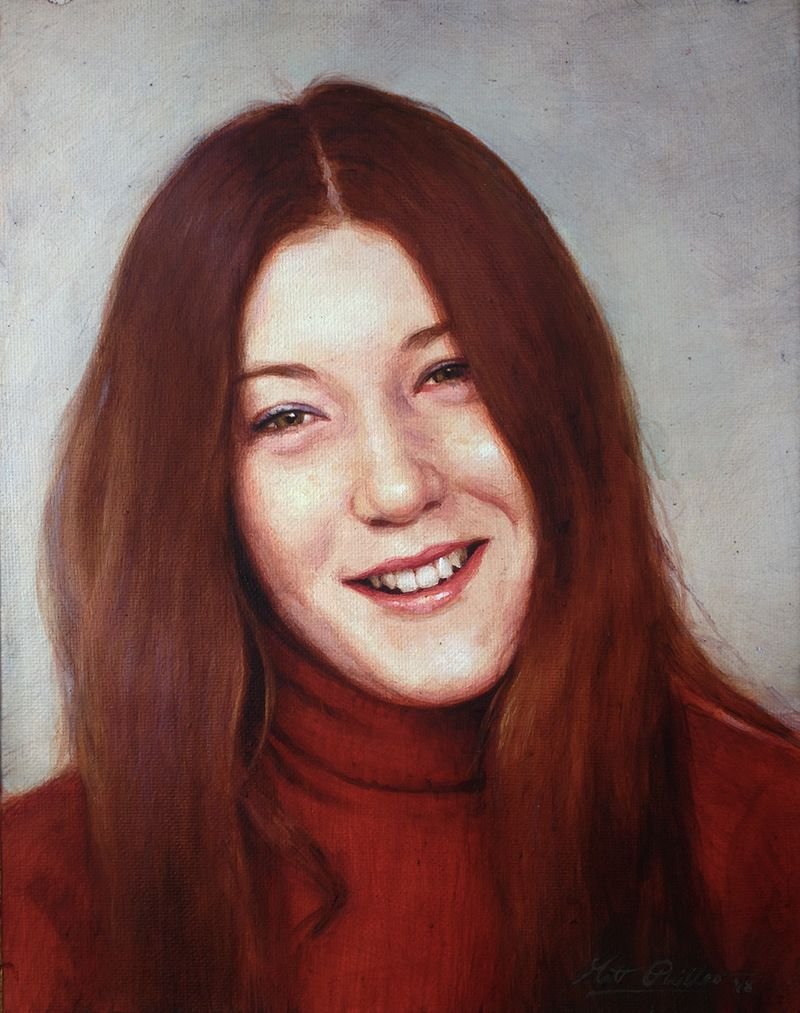

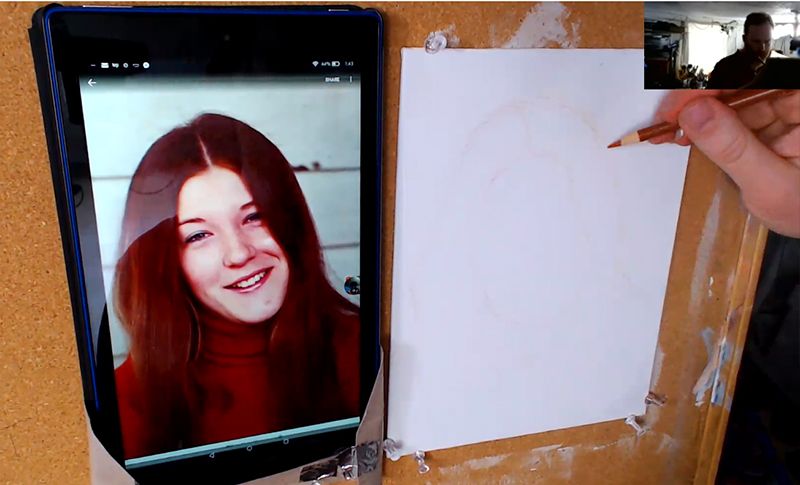

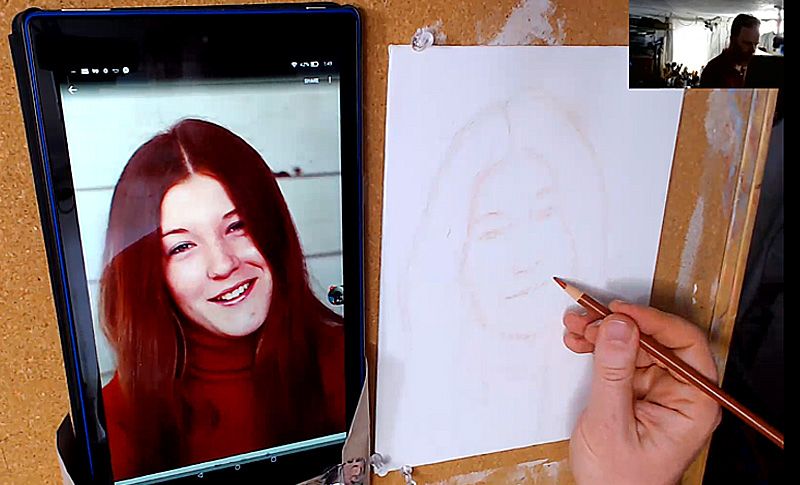

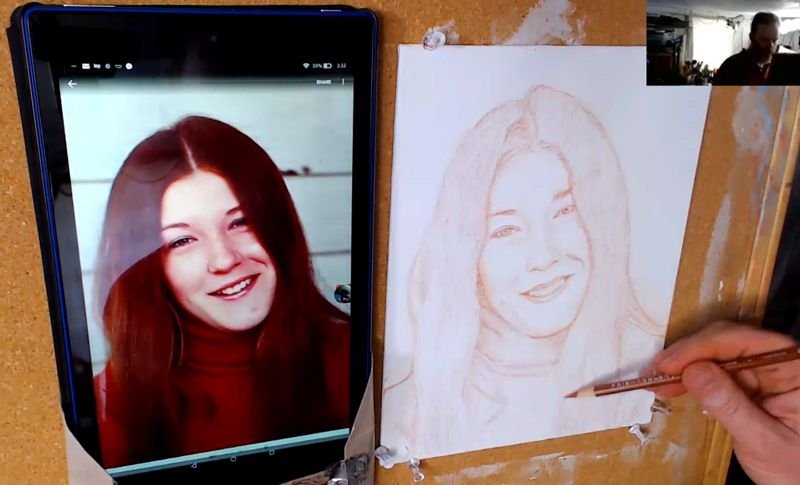

I’m not going to say I have the best method, but it has served me well in over 20 years of doing portrait art. I’d like to share that with you today, using this 8″ x 10″ commissioned portrait as an example…

Tools needed:

Canvas

Burnt Ochre Prismacolor colored pencil

Electric pencil sharpener

White smooth eraser

Here is the 15-minute video tutorial. The drawing took almost an hour.

The rest of this tutorial–showing the entire process, from sketch to finished acrylic portrait painting (about 7 hours of video instruction)–will soon be available as an online class. You can get access to it, and several other pre-recorded painting courses by becoming a member of Realistic Acrylic Portrait School.

Join Realistic Acrylic Portrait School TodayStep 1: Locking in the Composition

In this step, you want to plot out where your drawing is going. Here’s a few rules of thumb for a good composition and accurate initial proportions…

-Fill the image area as much as possible

-If you were to draw an imaginary line 1/3 of the way down from the top of the canvas edge, that line should go right through the middle of the face.

-Don’t let any major lines touch the edge of the “picture plane” (edges of the canvas)

-Look for the overall shape of the head: Is it oval? Long? Short and wide?

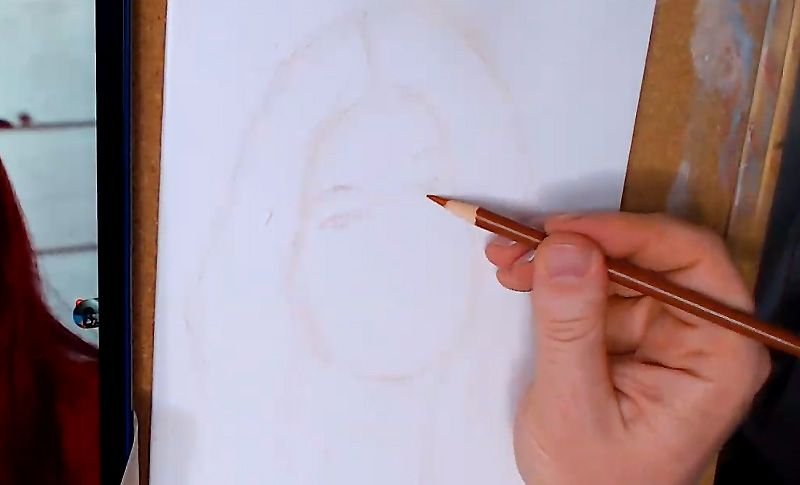

-Use light, short, choppy strokes to capture everything at first. It will be much easier to adjust and erase.

Step 2: Suggesting the Facial Features

After plotting out your composition, you want to start filling in the facial features. It’s good to draw lightly at first. We just want to get the basic location on the face and the overall impression of what they look like.

Start with the eyes. The eyes (and eyebrows) are THE most important feature to capture correctly on a face.

Ask yourself…

-Where are they located in relationship to the top and bottom of the head? Usually eyes are right in the middle, but that can vary from person to person.

-Are they large or small?

-Are they close together or far apart? Usually eyes are about one-eye-width apart from each other.

-Are the eyebrows straight or curved? Angled up or down? Thin or thick?

-How much of a distance is there between the eyebrows and eyes?

-What’s the shape of the eyes? Narrow? Rounded? Angled?

-How much of the top eyelid is showing? Some people have prominent upper eyelids. With others you can hardly see it.

-Are the eyelashes thick or thin?

Now, these questions will come more into play later on as you refine the sketch, but for now at this stage, just get the general idea captured.

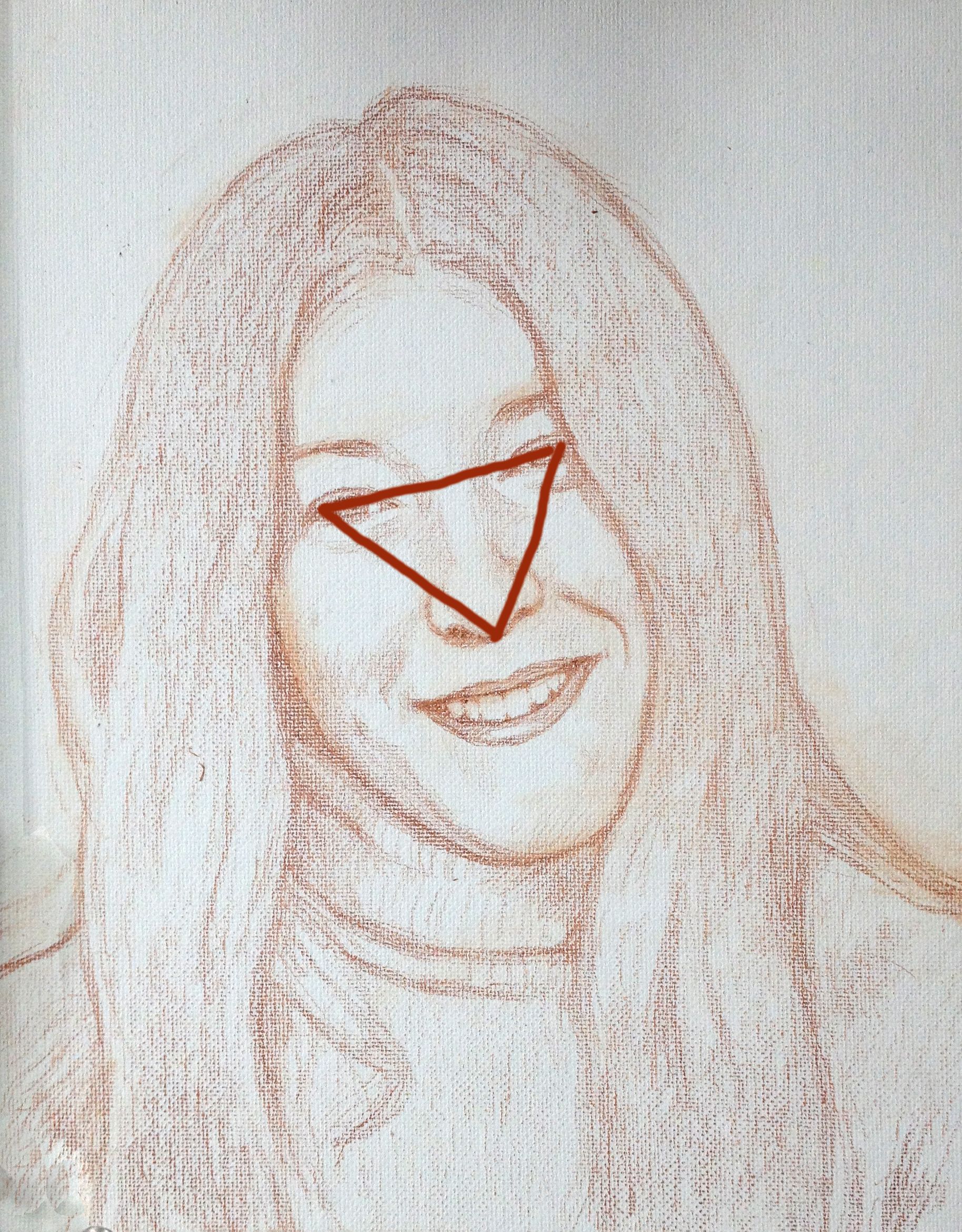

Next, you’ll move down to the nose. It’s important to see the distance between the eyes and the nose and draw that. The shape between the nose and eyes forms a triangle. If you can get a sense for that shape, it will really help you out. Is the triangle wide or long?

I am not saying to draw a triangle on your sketch. Just use the concept to see that spacial relationship between the eyes and the nose and draw it accurately.

Notice the particular shape of the nose and nostrils and draw it in. Are the nostrils prominent or obscured? Is the nose wide or skinny?

Then, move down to the mouth. You’ll want to just get the overall shape. Here’s some rules of thumb for drawing the mouth…

-The top lip is usually thinner than the bottom lip

-When smiling, the edges of the mouth usually line up with the middle of the eyes

-Don’t draw the teeth in too prominently. Just suggest them. Remember that the two front teeth are larger than the rest. -The bottom teeth, if showing, are slightly more than 1/2 the width of the top.

Step 3: Redefining the Facial Features

In this step, you will want to go over everything–the eyes, nose, and mouth: making sure your shapes are accurate. The overall size and proportions should be mostly locked in by this point. So what you’ll want to do is make sure the shapes on all the features match what you see in your reference photo.

Continue to ask yourself some of the questions in the previous step as you refine. And look at your reference photo 50% of the time to make sure you’re drawing what you see, instead of what you think you see!

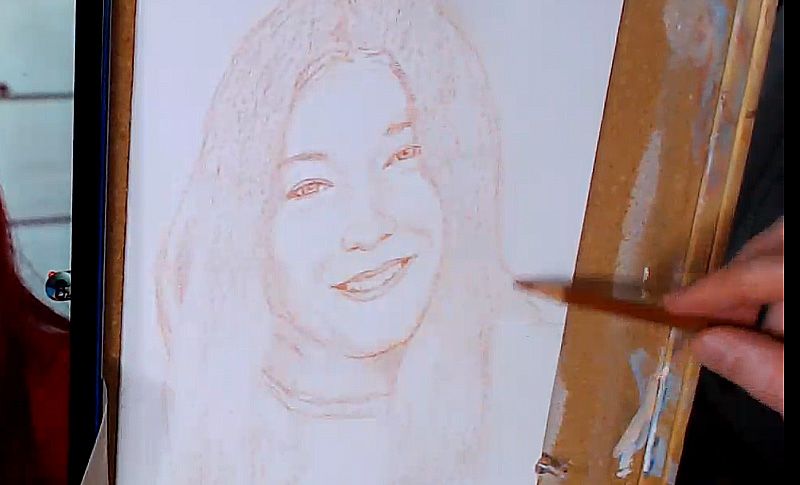

Step 4: Shading in

Maybe it seems redundant to shade in during a sketch, but I find it very helpful. We don’t see any resting objects in this three dimensional world as separated by line.

No.

It’s the contrast between value and color that tells us where an object begins or ends.

So, line is great for plotting composition and initial shape of features, but it is not useful for actually conveying a three-dimensional form on a two dimensional surface.

Which is why I like to shade in my sketches.

Shading will tell you how puffy a cheek is for example. Or how much a nose protrudes outward. Or how small a chin may be. And if you can capture that in the sketch stage (without too much fuss) it will really help you in the painting stage.

The heavy lifting will be done for you. All you’ll have to do in the painting stage is darken those shadows and add more nuances to tie them together. And of course, add color information!

I use the side of my pencil to block in the shadows in large areas. For smaller areas, I’ll use the tip of the pencil.

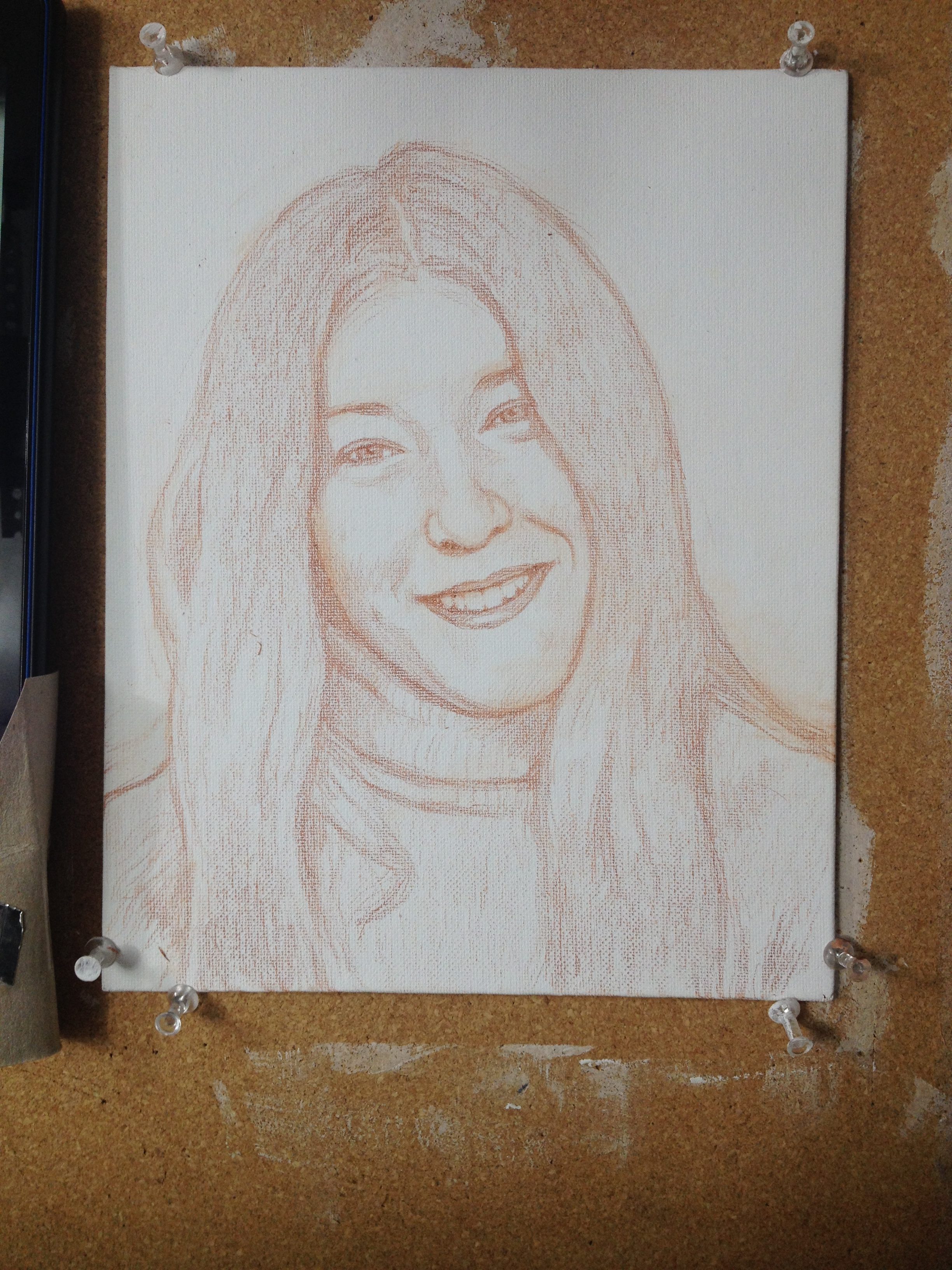

Step 5: Final Touches

The portrait sketch should be looking almost done at this point. Basically, you just want to go over everything, and make sure all minute proportions and shapes are accurate. The BIG proportions should be dialed in by now.

This step should take just a few minutes.

Keep in mind, you won’t get the sketch perfect. There may be a few areas that are getting hard to erase because you’ve drawn over the area so many times.

That’s OK.

Many small mistakes can be corrected in the painting stage. As long as you have everything close, you’ll be fine.

Once the drawing is done, you can step back and look at it from a distance just to make sure you have the likeness captured close enough. If so, you will have a good foundation to begin your portrait.

Have a blessed day,

P.S. Did you find this post helpful or encouraging? If so, send it on ahead! Let others know with the share buttons below. I’d love to hear your comments. Thank you so much! Also, do you have a question on acrylic portrait painting you’d like answered? Let me know, and I’d be happy to help!

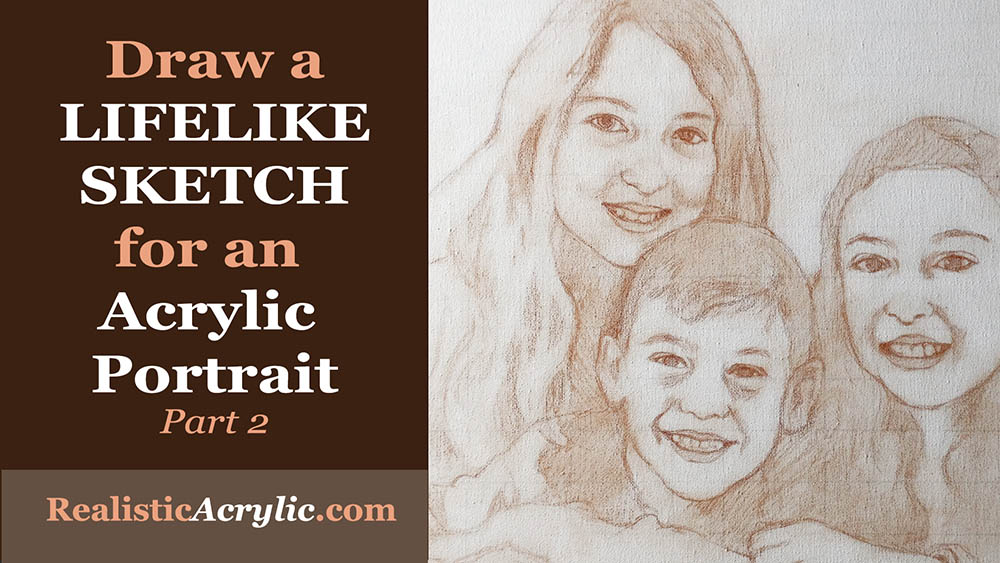

Draw a Lifelike Sketch for an Acrylic Portrait

Lifelike Sketch + Accurate Acrylic Layers + Patience= Realistic Acrylic Portrait. The equation works every time.

Even when you make mistakes. 🙂

Don’t worry, this won’t be a math lesson. That was not one of my better subjects in school!

But there is something to be said laying down a good foundation for your acrylic portrait with a lifelike sketch. When I mean lifelike, I don’t mean that it looks photographic, but rather that you capture the likeness of the subject–the person (or pet) you’re going to paint.

When you do that, you exponentially increase your chances for success in painting a realistic acrylic portrait.

Notice I didn’t say perfect. You don’t have to have a perfect sketch, just one that is as accurate as you can make it.

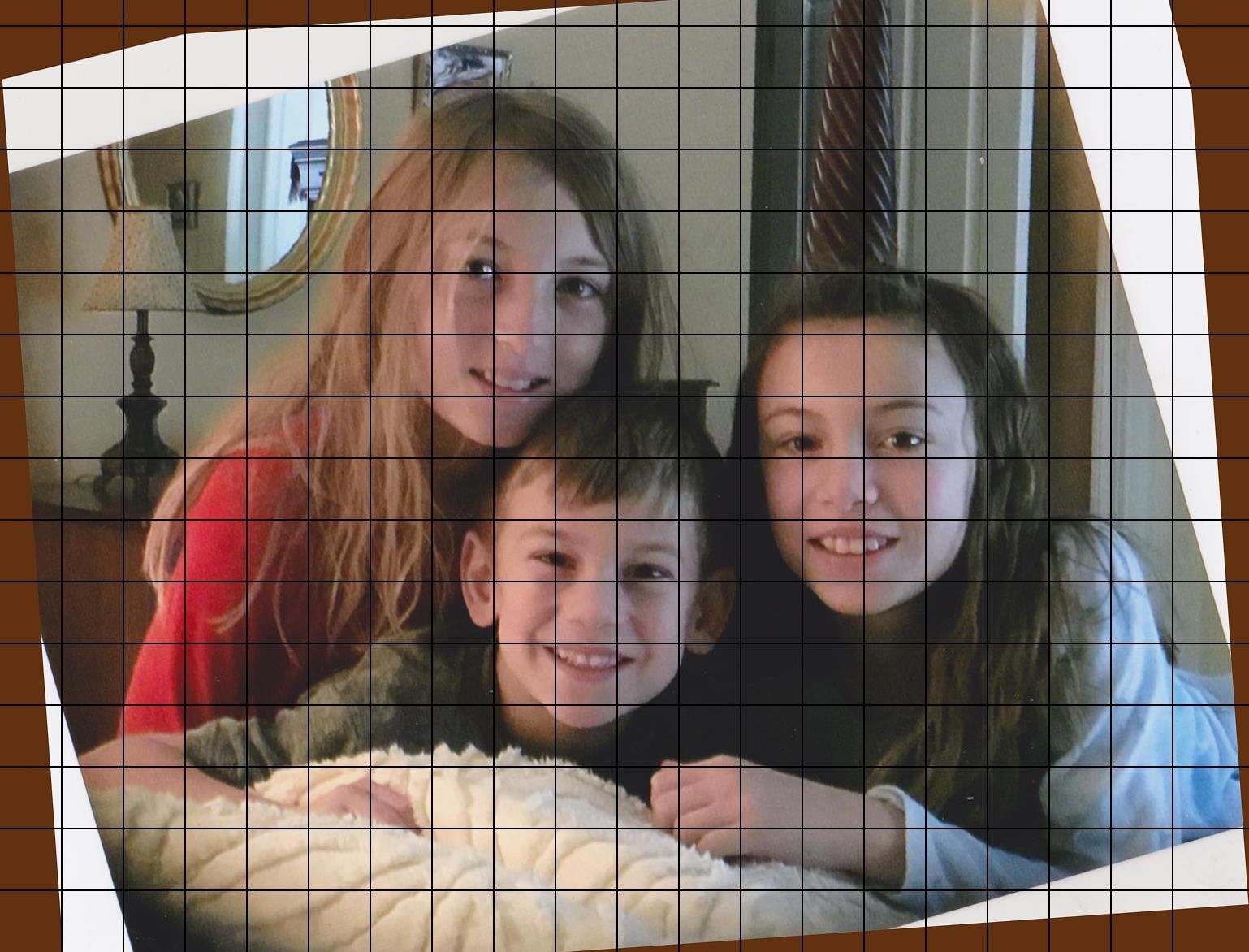

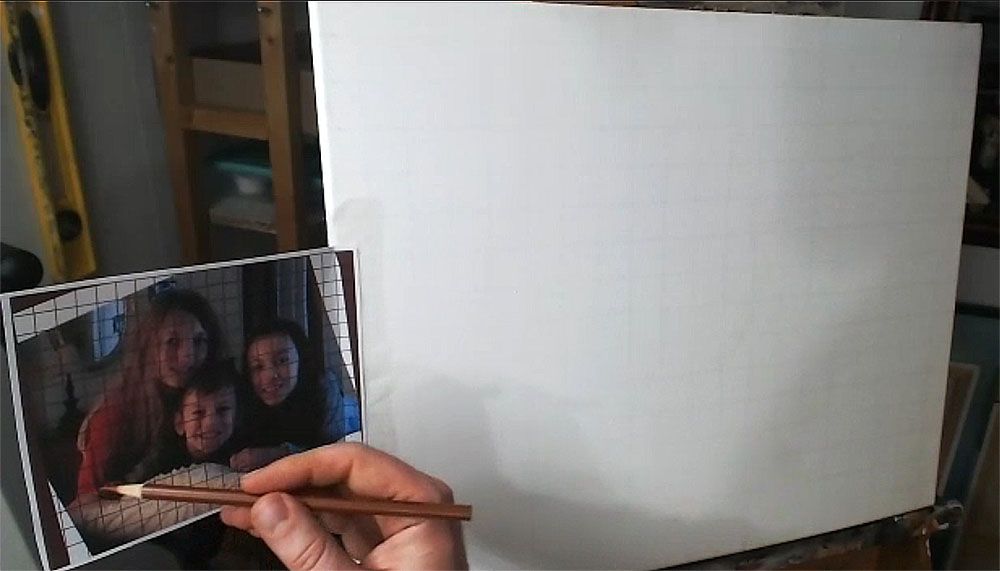

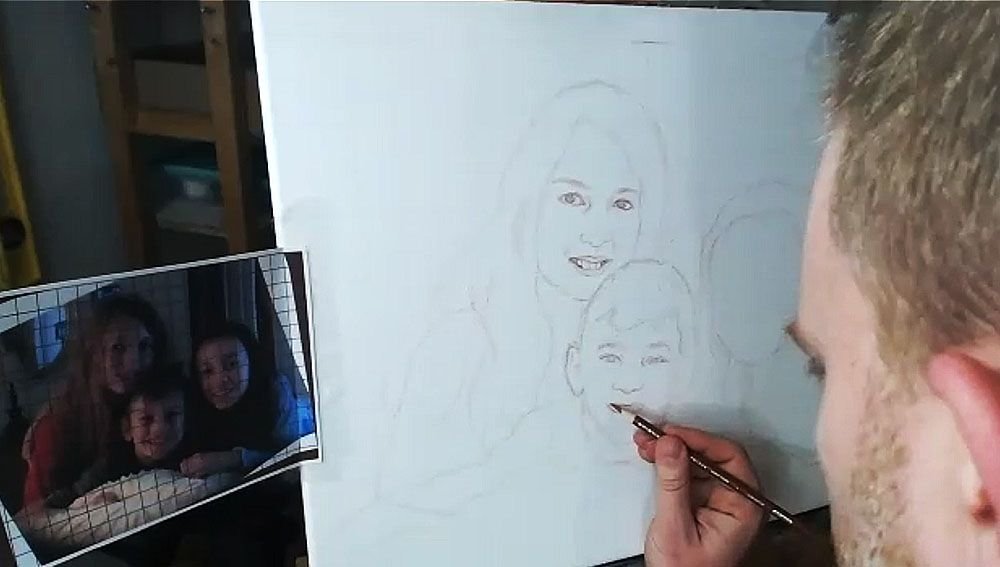

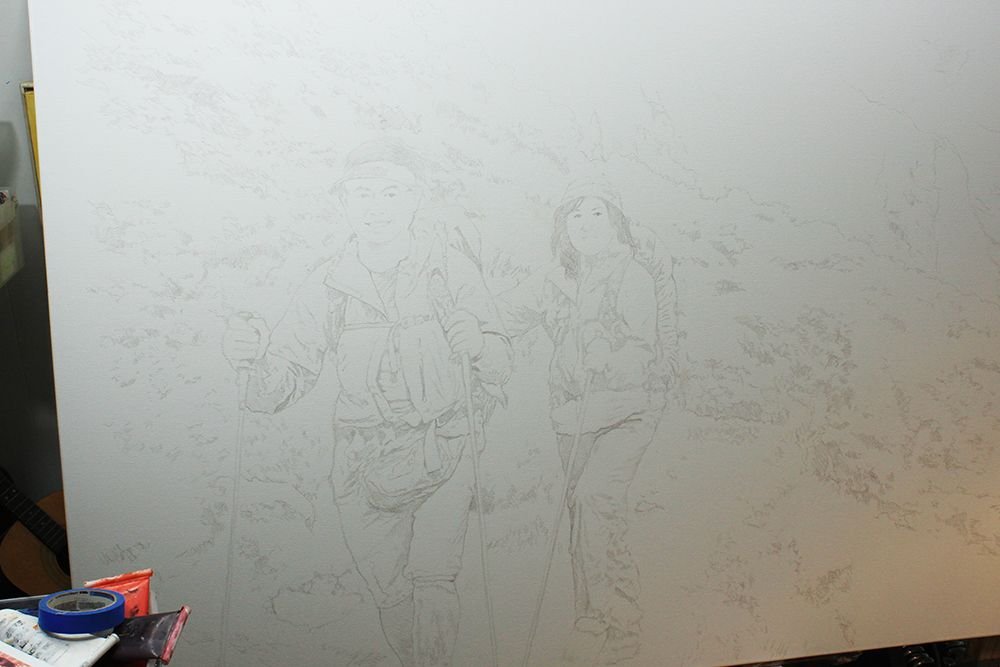

Today, I’m going to show you how I drew the sketch for a commissioned 16″ x 20″ acrylic portrait I’m working on of three children…

…based off a candid photo of them just hanging out on a bed. I tilted the image because I thought it was at an awkward angle. You can obviously see the original angle in shown in the edges.

Tools Needed:

You’ll want to use a sepia-toned colored pencil, like burnt ochre, dark brown, or terra cotta.

And then a white eraser.

I started with a canvas that I drew a grid on–with 1″ squares, using a light colored pencil (light grey, tan or peach is fine). It is important to seal the grid in with a mixture of matte medium and gesso. This provides a barrier on the canvas so that when you need to erase anything on your sketch, you will not disturb the grid lines beneath. Also, it makes it amazingly easy to erase a sketch on your canvas–much easier than graphite pencil. This is a technique I discovered just by being frustrated with pencil and experimenting.

The photo reference is also gridded correspondingly to match the squares on the canvas. I used a grid drawing tool at ArtTutor.com and then printed out the image.

Alright, now let’s begin…

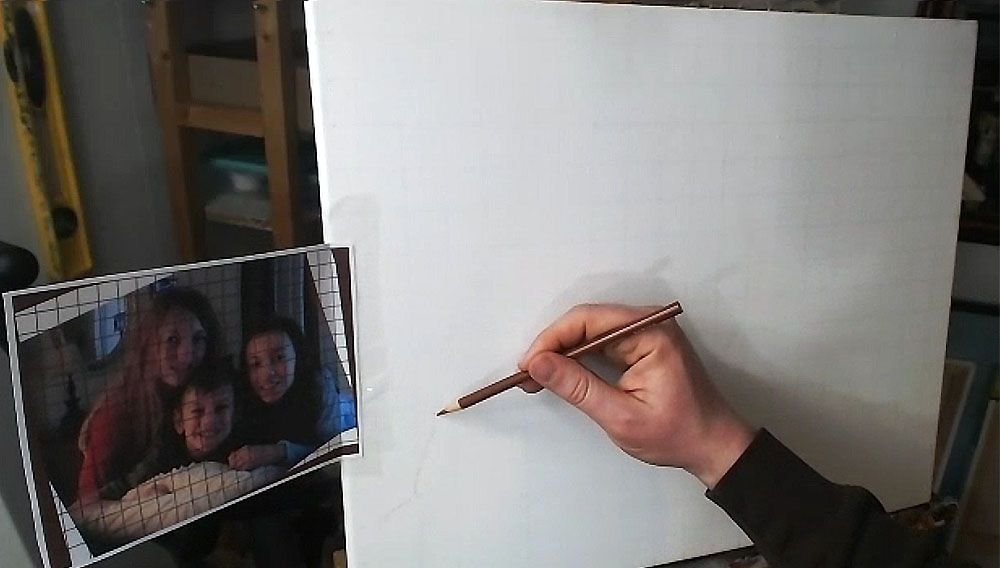

Step 1: Get Started in the Right Place

When using the grid technique, it’s so important to make sure you start sketching in the right place. Otherwise, you may end up sketching for a while, only to realize your composition will be off.

Yes, I made this mistake.

So, count off your squares, and double-check that you’re matching up on your canvas, what is on your reference photo.

Watch this video to see the beginning portion of the sketching process…

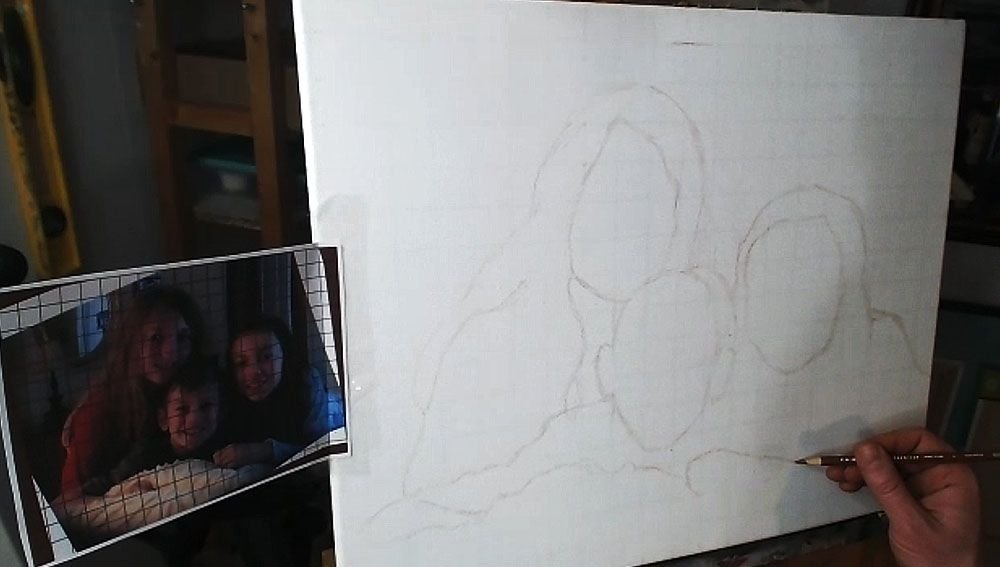

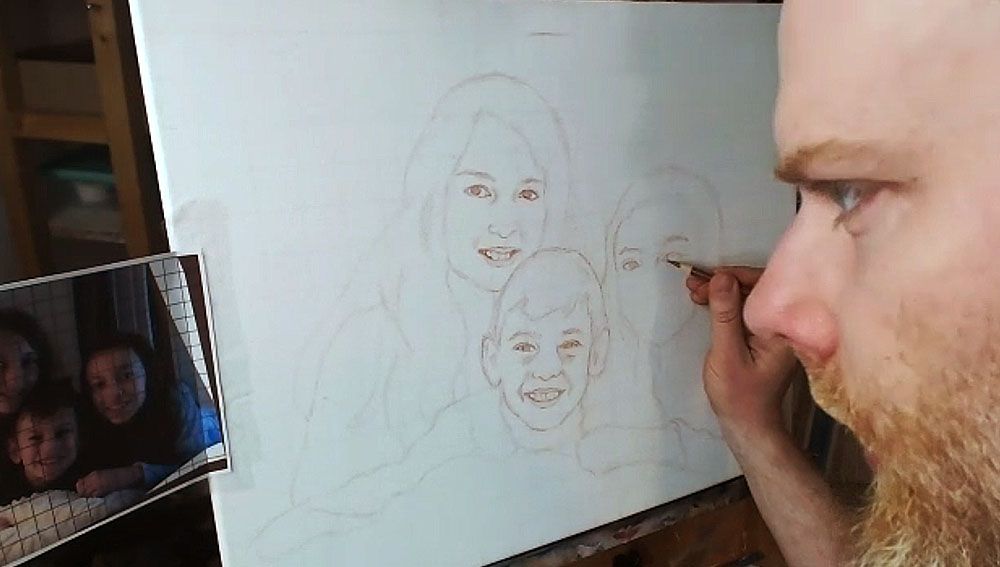

Step 2: Start Your Outlining the Forms of the Subjects

Here, we only want to get just the outside edges of the subjects and then fill them in. I start usually in the lower left corner and then work my way up and across. You don’t need to achieve perfection in this. But it is good to see where the major lines representing the shapes are intersecting the squares. Break it up into fractions.

(Uggh, math again. It’s OK. If I can do it, so can you, believe me!)

You note, “Okay, this line crosses through the vertical line of this square at about 1/2 of the way up.”

Or, “this line intersects the horizontal line of the other square about 2/3 of the way to the edge.”

You may see fractions like 1/4, 1/3, 1/2, 2/5, etc. You’ll begin to see them naturally and not even think about it with some practice. When you learn to do this, your gridded sketching will become very accurate.

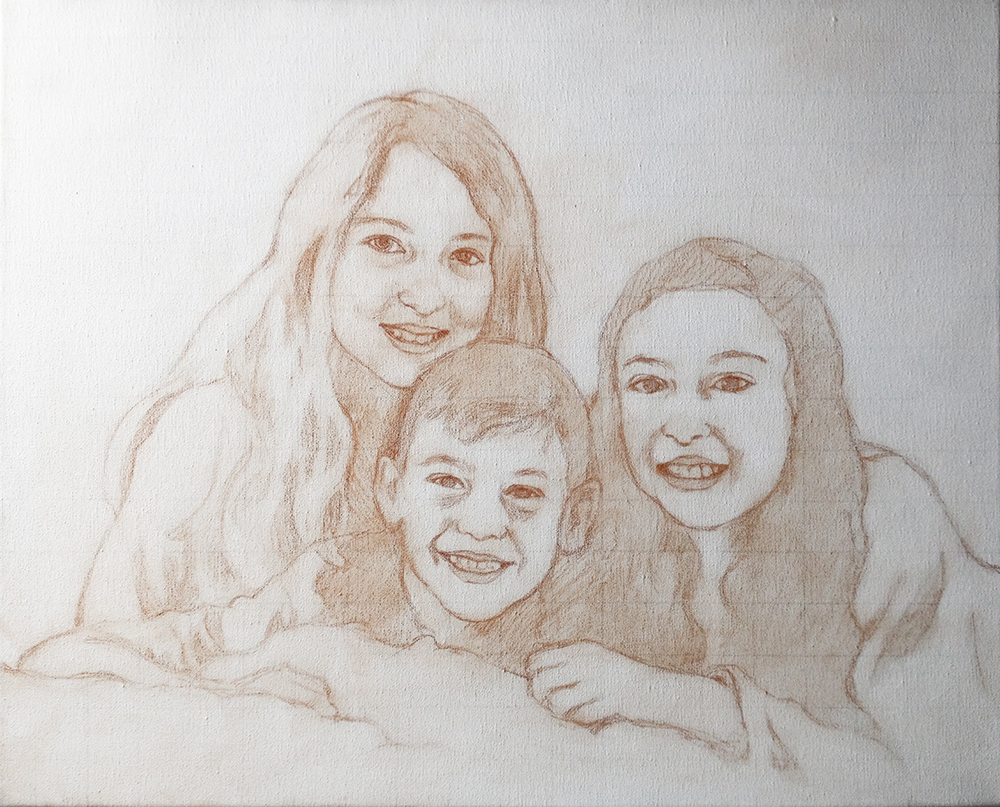

Here is the sketch, with all the outlines filled in.

You’ll notice that I made a pretty large mistake, but thank God for erasers! I considered editing it out of the video, but then I figured, “Why not keep it in there, to show an accurate recording of my process?” We all make mistakes, but it’s what we do after we notice them that counts.

Step 3: Fill in the Features

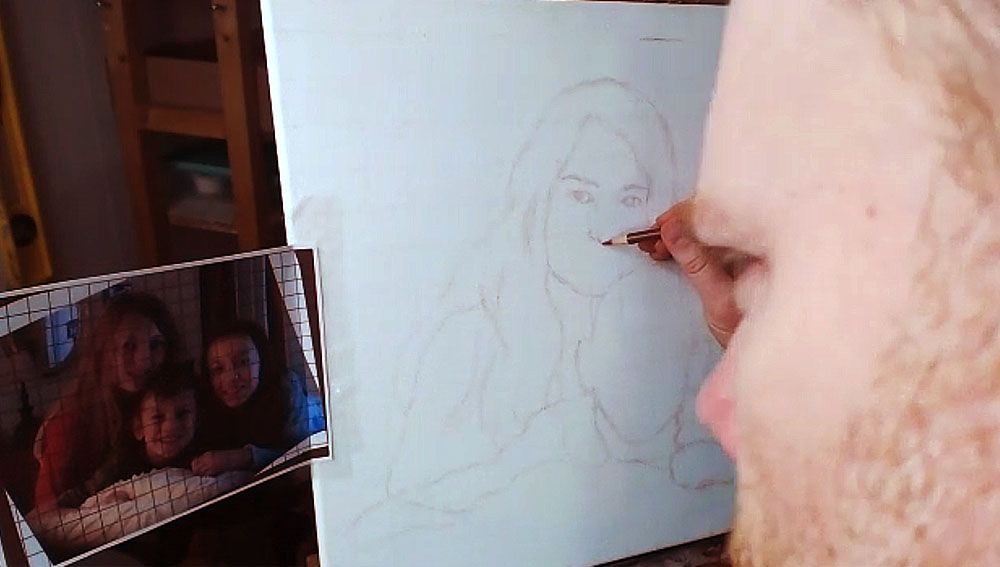

After getting the proportions of the subjects in correctly–the outside edges of the hair, the shoulders, the faces, etc., then you’re ready to move on to drawing the features. The reason we get the main forms defined first, is because we want to make sure we have an accurate foundation to drop the features on. In addition, you’ll be able to tell if you like the overall composition.

Now, when I start drawing in the facial features, I work from left to right, and then top, down. (Of course, if you’re left handed, you may naturally work in the other direction.)

I start by noting the angle of the eyebrows and sketch them first. Doing this will really establish the alignment of the face and your other features will need to be in conformity with it.

Then I draw the eyes loosely, and not too dark, so I can refine them later. The eyes are the most important feature on the face, so I really pay attention to them.

What is the overall shape? Are they skinny, angled, rounded? Are there prominent eyelids or are they barely perceptible? How far away are they from the eyebrows? How close are they together? Ask yourself these questions as you draw.

If you can get the eyes about 85% or more accurate, you’ll have a good portrait.

If you can get them 95% or more accurate, you’ll have an outstanding portrait, provided the other features are drawn fairly well.

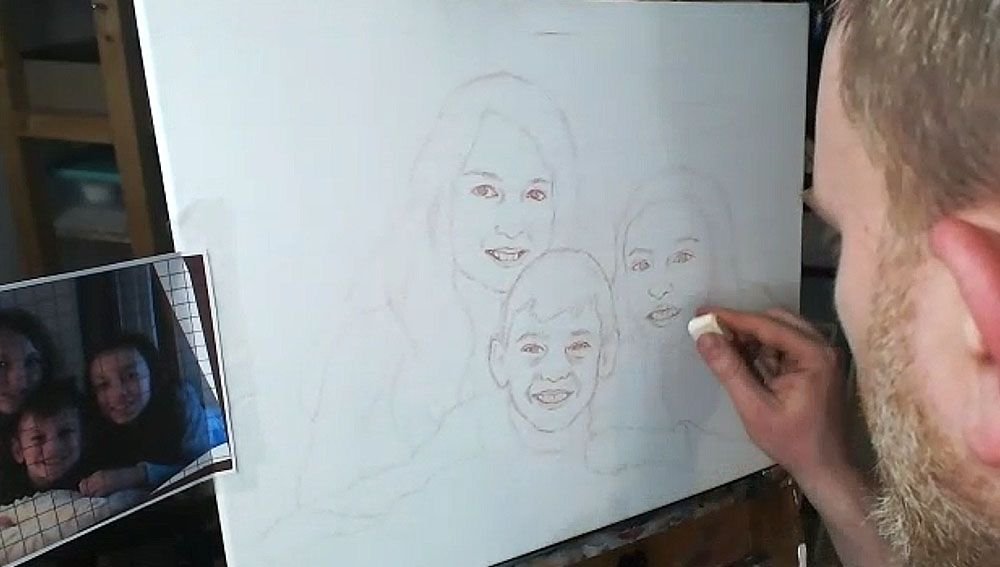

Next, draw in the nose. Observe your reference photo to see how far down the bottom of the nose is from an imaginary line that intersects the eyes. What is the shape of the nose and nostrils? Is it wide, narrow, rounded, sharp? Observe carefully and draw what you see.

After you get the proportions and shape of the nose accurately defined, it’s time to move on to the mouth.

I start with the top of the mouth, drawing in the bottom edge of the top lip and then the top edge of the bottom lip. I sometimes will draw the top edge of the top lip, if it’s very prominent–like, for example, when a woman is wearing lipstick. Of course, that is not the case for this drawing of three children.

I finish with the bottom edge of the bottom lip. Of course, I also draw in the teeth, but only lightly suggesting their form by showing the gumline, and the shadows on the sides where the teeth are foreshortened in perspective, and the lips cast shadows on them. The space between the visible teeth and the edges of the mouth is very important, and you’ll want to indicate it as a dark value, because it is in shadow.

One of the main mistakes I see artists making in their sketch is when they over-define the teeth. It makes the person you’re drawing look like they have braces. Pencil lines are just too dark of a value for the teeth, and it’s hard to overcome in the painting. Draw them lightly, and you’ll get better results.

Watch Part 2 of my video lesson below to see exactly how to do it…

After I get the features sketched in loosely and lightly, then I go back over everything. I darken and refine.

I repeat the process on the other faces.

TIP: Look at your reference photo often as you draw–much more than you are currently. At least 30% is a good rule of thumb.

I can tell you from teaching portraiture in person, that students only rarely look at their reference photo. But you can only draw what you are observing, so observe more and draw better.

But if you make a mistake, you can always use an eraser!

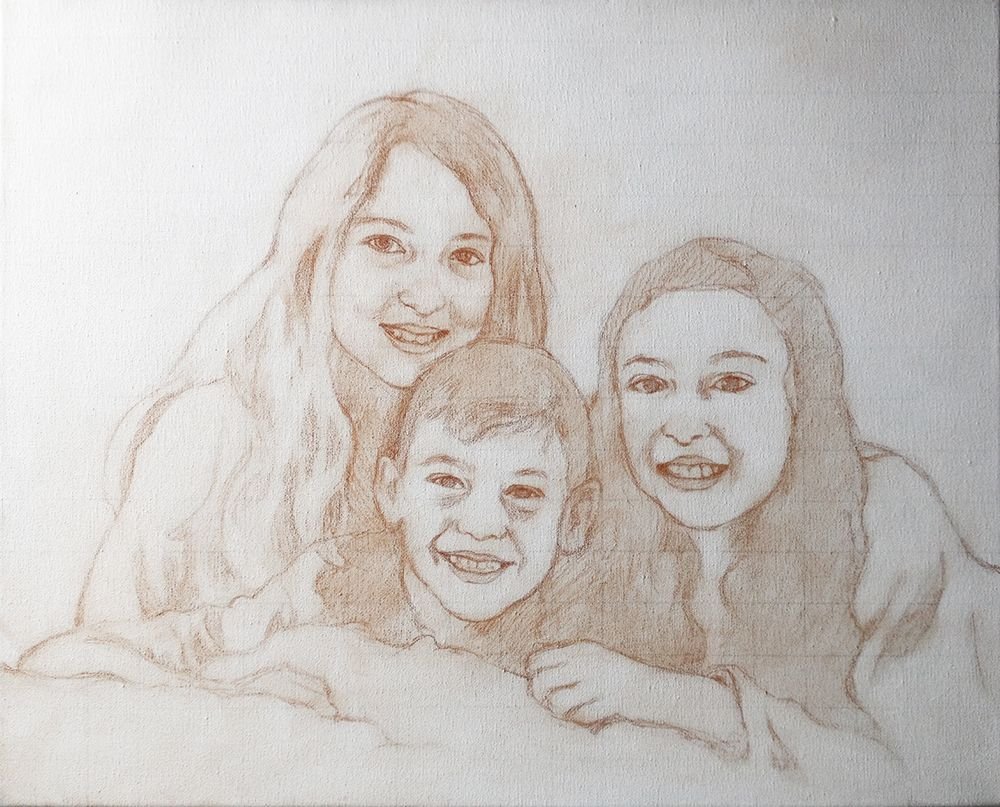

Step 4: Finish Off the Forms

After filling in the facial features, I draw in the hair, hands, wrinkles for the clothing suggesting the shoulders and arms.

Step 5: Shade in the Major Values

Everything we see in the three-dimensional world is viewed in the context of differences in value and color. There really aren’t lines separating anything in nature, even though the concept of a line exists in geometry and we can obviously draw them.

So, with that , I feel it’s important to define the major values in your painting during the sketch stage. You’ll be much better prepared when you start painting. You won’t have to wonder subconsciously, “What do those bunch of lines represent?”

The values will let you know where to apply your first layers in the blocking-in stage of your painting. You can dive right in and do it.

So I fill them in, using the side of my pencil lead, rapidly. It doesn’t need to take much time. I just try to see the major areas of contrast, like the shadows under the faces, wrinkles in the clothing, locks of hair that aren’t illuminated, and represent it on the canvas.

Lastly, you can double-check the facial features on everything, and make sure it’s accurate.

And here’s the final sketch. Not perfect. But close enough that I can rectify any mistakes in the painting and bring it closer to a very accurate likeness.

I’ll be showing more of the process of this painting, breaking it down step-by-step and teaching you as I go along. I look forward to sharing more with you !

Have a blessed day,

P.S. Did you find this post helpful or encouraging? If so, send it on ahead! Let others know with the share buttons below. I’d love to hear your comments. Thank you so much! Also, do you have a question on acrylic portrait painting you’d like answered? Let me know, and I’d be happy to help!

A 48″ x 72″ Commissioned Portrait Adventure, Part 2

Last week, I shared with you the beginning of my adventure on painting a huge 48″ x 72″ portrait.

Thank you so much for all your kind words and feedback on this project!

In that post, I mentioned how I tracked down the canvas, brought it back, and then created a layout for the portrait with Photoshop.

Today, I’m going to show you the sketching process, and with that, maybe spark a little controversy! 🙂

Controversy? How can sketching be controversial?

Well, there’s a huge debate in the artist community on tracing/ using projectors and whether or not it is cheating.

I’m going to show you the process I used and argue that it is not cheating. But I am open to discuss it.

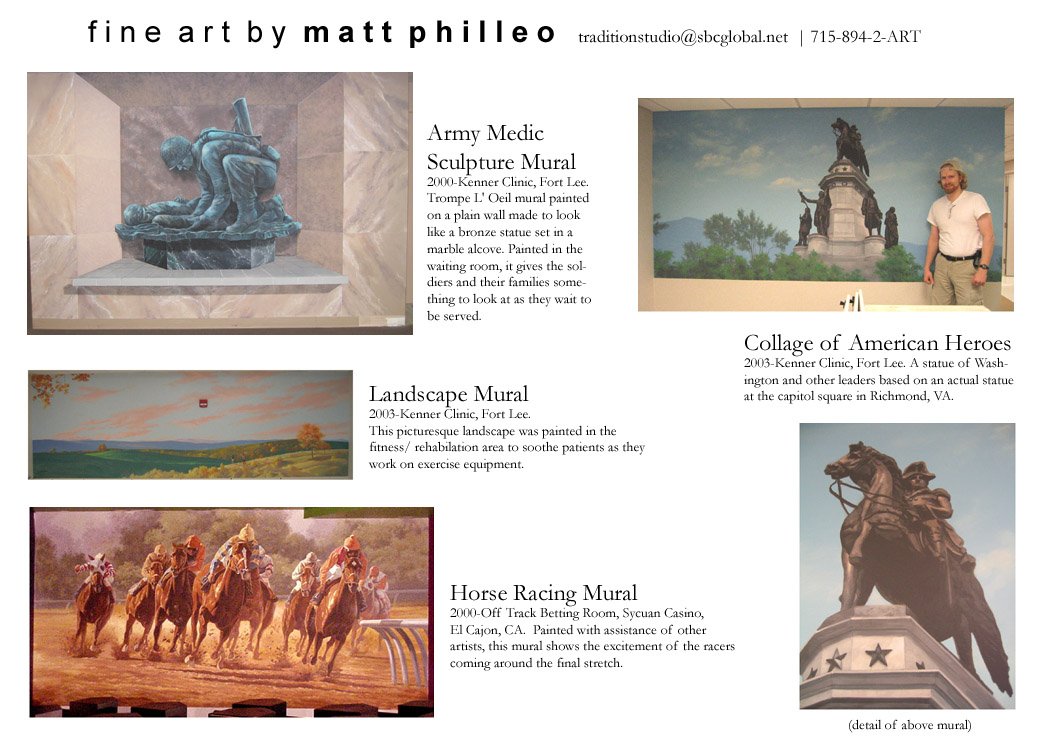

First of all, I wondered with this big canvas, “should sketch on it using the grid method, or even freehand?” I’ve done hundreds of freehand sketches for portrait drawings and paintings, and in fact, it was the only way I ever drew anything from my childhood up until I started doing murals in 1999, when I was 22.

Then, through a contact I made while studying at the Milwaukee Institute of Art & Design, I got in touch with Bob Jenny, a prolific and successful muralist from Ft. Lauderdale. We did several murals together, starting with two 6′ x 30′ murals in Womack Army Hospital in Fort Bragg, NC, and then a couple in Kenner Clinic in Fort Lee, VA.

Here are some images of those murals…

“You paint like an artist!” Bob chided me when he saw my technique. I used tiny brushes, piddling away on a large surface.

It would be like trying to paint your average 16″ x 20″ portrait using toothpicks.

Not only that, but I attempted to sketch out an expansive scene of the army medic serving in World War I & II in freehand on the hospital wall.

It looked good, but it was taking way, way too long. It wasn’t just a matter of it eating into our profits, but it was also the fact that there were many contractors working in the hospital, and the thing had to be done by a certain time.

So Bob showed me how to paint like a painter. He taught me how to use large brushes and even a roller to cover large areas quickly and effectively.

For setting up the sketch, Bob instructed me to use a projector. Some artists spend a fortune on snazzy art projectors that can project a regular photo print on the wall, but Bob used just an overhead projector–the kind that people used for teaching and media presentations, “back in the day” before PowerPoint became the thing.

You just make a transparency of your photo reference at your local copy shop and you’re ready to go. Or, you can buy transparency film that runs in your inkjet home printer and make your own.

Using the projector on a mural or large painting saves a ton of time. It’s very difficult and time consuming to get accurate proportions drawing freehand over a large surface. Your brain just can’t see the whole picture. So, I learned to use a projector while working with Bob, and it’s been great for quickly getting a sketch up on my canvas or panel.

Some artists feel like it’s cheating.

I don’t.

I see it as a tool. It’s the same way you would expect a carpenter to use a ruler, level, clamps, power saws, power sanders, nail-guns, etc. to get his job done quickly, reliably, and effectively.

But as an artist, you don’t want to use it all the time. It’s important to learn how to draw freehand as well. You can use a grid to start with. And then go completely freehand as you gain confidence. These drawing skills will translate into painting skills–because painting a realistic portrait is always fighting the internal battle of painting what you actually see, rather than what you think you see.

If you want to paint a portrait from a photo, and do it well, it will be a lot easier if you learn how to draw.

With this 48″ x 72″ portrait, the size is large enough that I decided to use a projector to accurately transfer my Photoshop design onto the canvas. I thought about using the grid system for a moment, but I decided it would take too long to set up all the grid lines, seal them in, and then try to mask them out at the end after doing the sketch.

The figures in the portrait just have too much detail for that to work, not to mention the background.

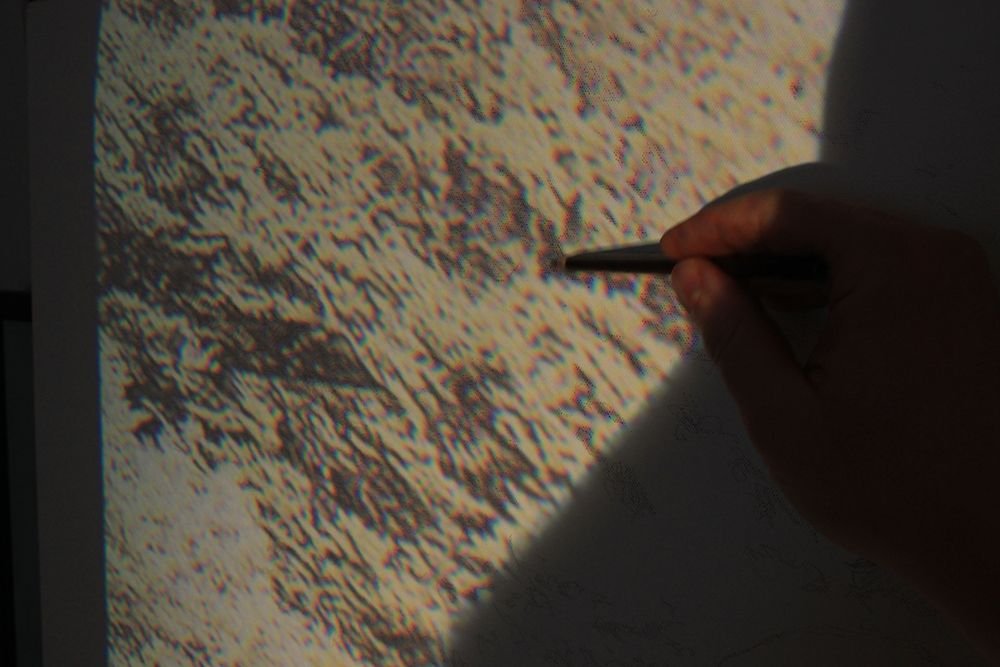

So I set up my projector. I use an Apollo Horizon 2, which I purchased for about $200 several years ago.

I printed off the design on my inkjet printer and then laid it flat on the surface of the projector.

Now, you will find that the lightweight plastic sheet will want to curl on you from the projector’s heat. So, if you put a piece of glass on the top (I tape the edges with masking tape, so it doesn’t cut me by accident) it will be enough to keep your transparency in place.

After that, I set up my canvas vertically against the wall. I have pretty small studio, but the room is long, so I faced it so I had room get the projection lined up straight on the canvas.

Next, I turned on the projector and lined it up. There were a few inches on either side that I couldn’t cover, but that would be easy enough to fill in later. Also, I needed to move that chair out of the way! 🙂

I used a sepia toned-colored pencil to do the tracing. I work from the left to the right, keeping my body from obscuring the projection.

You would think that tracing is just a mindless process, and so simple that a caveman could do it. But you have to discern what lines are important and what are excessive.

Why?

The projection will take the image and flatten it out. Background, foreground, subjects all become a jumbled mess of contours and details. You will lose discernment over what you’re actually tracing when you are close to the image. It’s good to hold a printed image of what you are tracing, or tape it up next to your canvas. That way, you’ll see the whole picture and if you can’t tell what it is that you are tracing, you’ll get a clue from your reference photo.

It’s good to fill in some of the shadow areas even while tracing, or you’ll have a tough time recognizing what the lines represent visually, when you shut your projector off.

It took me over an hour just to trace everything. And with that, my work only had just begun.

When you have a tracing done, you are not finished yet. Not by a long shot.

This is where your freehand drawing skills come into play. If you want an accurate sketch as a solid foundation for your portrait, you have to go back over the tracing and enhance it.

You may be able to pin-point where the eyes or mouth are on the face with the projected image, but you’ll have to actually draw their shapes in. You’ll need to take the jumbled lines representing the background and subjects and add detail to them. The projection just won’t do that for you. All it does is give you the overall composition and proportions.

You’ll also need to darken some of the lines, and leave other lines light.

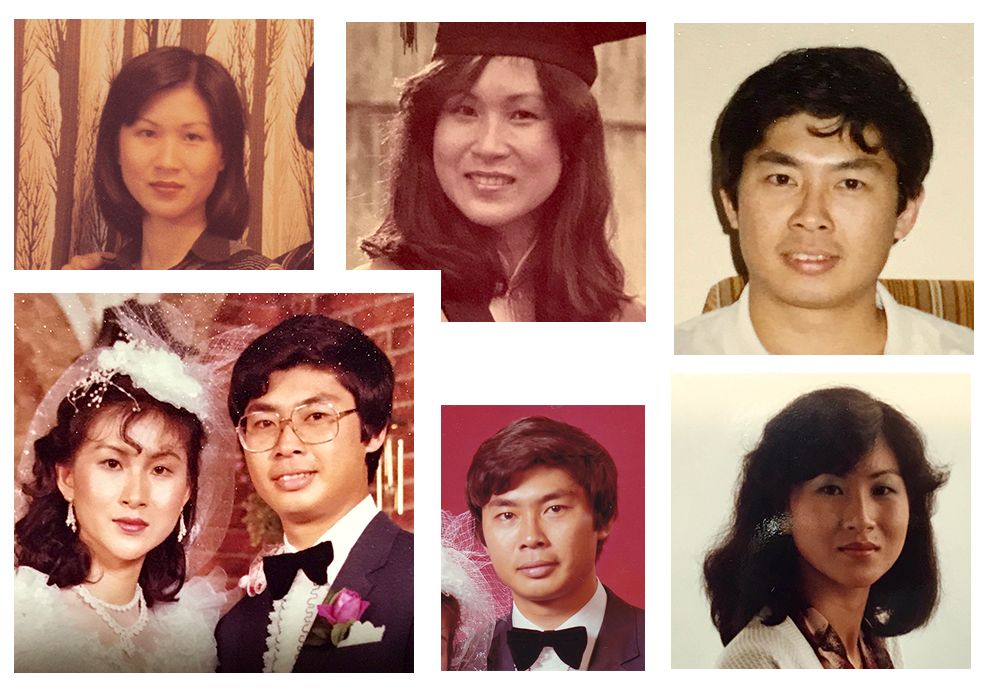

That’s what I did with this picture. In addition to that, the client wanted some changes. I think I mentioned that in my previous post. He wanted he and his wife to look younger, and their sunglasses to be removed.

So, after I finished the tracing, I put in a couple hours changing their faces, using reference photos that the client supplied as a guide.

I also refined the details of their clothing, supplying the visual information that the projection left out. I went into the background, making sure I could identify what were the edges of hills, and what was just foliage within the hills.

I defined the edges and rock formations within the waterfall, because in the tracing, I could only make out just a couple angles and nothing more.

Finally, after about five hours or so, I’ve got the sketch finished!

The client has approved it, and now I am ready to paint. I’ll share that part of the adventure next time. ‘Til then, have a fantastic Easter/ Resurrection Sunday, and I’ll be in touch! (Here is a video I recorded where I talk about a mural that a friend and I painted that goes along with the Easter theme. Enjoy!)

Be blessed in your painting and creative ventures…

All the best,

P.S. Did you find this post helpful or encouraging? If so, send it on ahead! Let others know with the share buttons below. I’d love to hear your comments. Thank you so much! Also, do you have a question on acrylic portrait painting you’d like answered? Let me know, and I’d be happy to help!